What Happened On China's New Silk Road In 2017

Field notes from the front lines of China's Belt and Road.

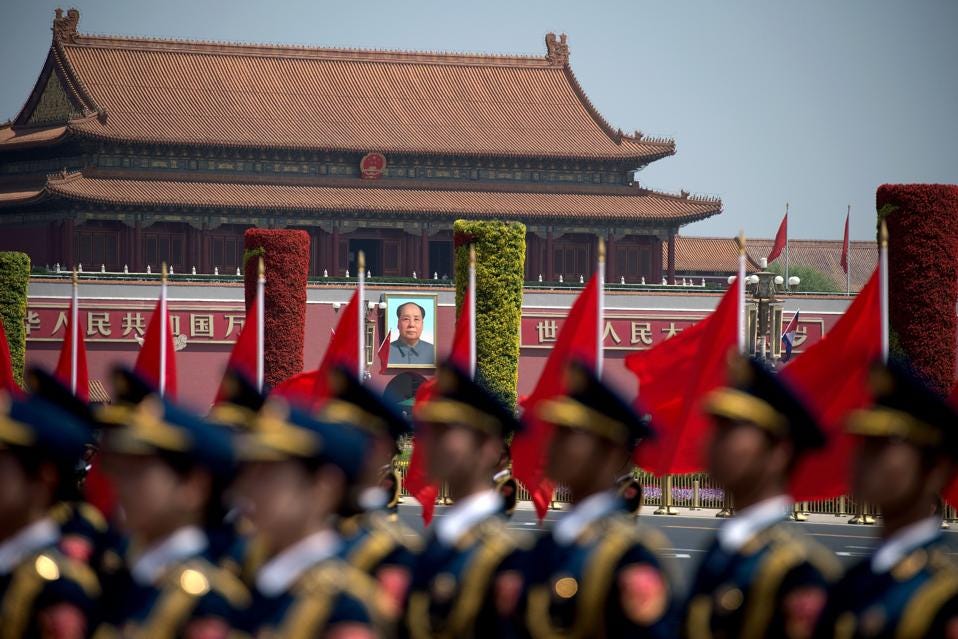

(NICOLAS ASFOURI/AFP/Getty Images)

Year four of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is now in the books. The purpose-built, ground breaking’endeavor to insert China as the connective tissue between most of the other countries of Eurasia and Africa is no longer the new geopolitical kid on the block, and we are starting to get a good look at what this thing is really all about beyond the rhetoric and propaganda:

The BRI can ultimately be deduced to a series of unconnected but nonetheless related bilateral trade and development deals which China is making either one-on-one or group+1 with countries and political blocs across Asia, Europe, and Africa. There is no overarching structure, no membership protocols, no moralistic browbeatings, no predefined set of standards that BRI participants need to uphold in unison ... Each country or bloc negotiates on their own terms, and deals can be structured in accordance with each set of particular parameters.

Basically, rather than being a cohesive network of countries working together on “win-win” partnerships under a collective framework, the BRI is turning out to be a slightly catchier stand-in for “bilateral deals with Beijing.” It remains, by design, a mere initiative rather than a coherent strategy, as Jonathan Hillman of the Center for Strategic International Studies pointed out:

An initiative has the benefit of being viewed as less threatening, more open ended, and more inclusive than a strategy. But it also lacks the focus, coherence, and substance of a real strategy. The distinction between initiative and strategy is more than simple semantics. It captures the central challenge the Belt and Road faces.

Who the Belt and Road is for

In 2017, in addition to being able to start to see what the Belt and Road really is, the world also got a good glimpse of who it’s for: shadowy state-owned firms with ambiguous acronyms that start with the letter C: COSCO, CREC, CRCC, CNGC, CMG.

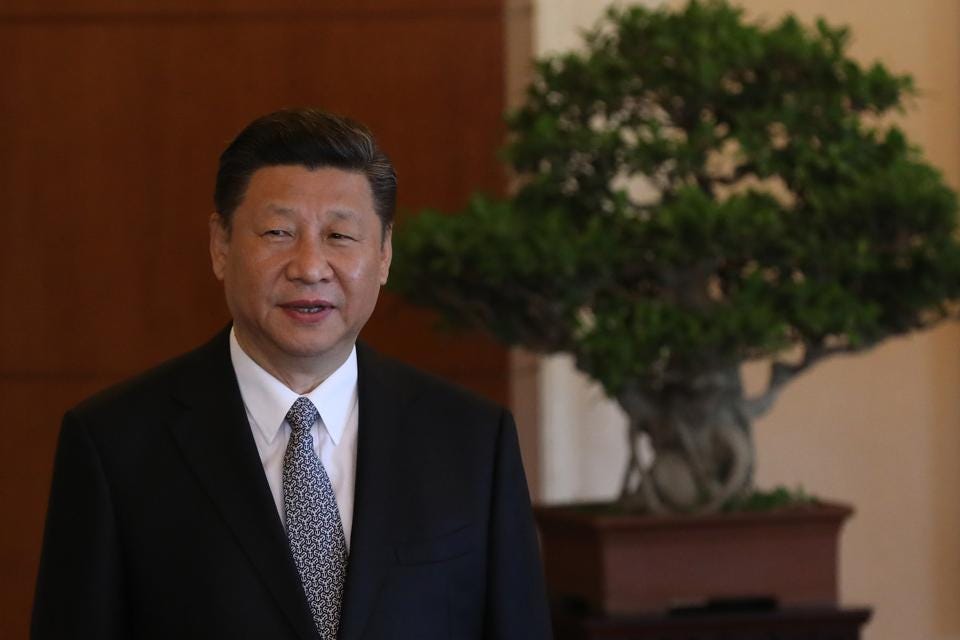

After a couple of years where many of China’s big private companies took to foreign business arena like kids set free in a theme park — buying this, acquiring that, and getting torrents out RMB out of the country under the name of the Belt and Road Initiative -- President Xi Jinping stepped in with a major crackdown on what he termed “irrational investments.” China’s banking regulators were sicked upon at least four major companies who were responsible for a full 18% ($55 billion) of China’s foreign investments over the past two years -- HNA Group, Anbang Insurance Group, Fosun International, and Wanda -- shutting down their plans for further international expansion. Wanda Chairman Wang Jianlin, who once reigned as China’s richest man, was publicly called out by Beijing and then probed behind the scenes, which ended with him promising to refocus his investment activities in China’s domestic market and to sell off a good chunk of his assets to repay his loans.

(NICOLAS ASFOURI/AFP/Getty Images)

By constitutional decree

Further consolidating control of the Belt and Road in the hands of Beijing, the initiative was etched into China’s constitution in 2017 — right alongside “Xi Jinping Thought.” Where the U.S. Constitution has essentials in it like freedom of speech and the right to bear arms, China’s now has “... following the principle of achieving shared growth through discussion and collaboration, and pursuing the Belt and Road Initiative.”

The first BARF

Perhaps the biggest political demonstration of the Belt and Road yet also happened in 2017. The first Belt and Road Forum (BARF) kicked off in Beijing in May. The unfortunately acronym-ed event brought 28 heads of state, 100 lower-level government officials, dozens of major international organizations, and 1,200 delegates from various countries into Beijing to talk about the future of the Belt and Road. Many deals were signed, Xi Jinping gave a speech, and political capital was exchanged all around -- but when the dust cleared everything seemed very much the same as it was before: the BRI remained vague and murky, subject to various interpretations, and lacking any sort of institutional framework.

The Belt and Road is a bunch of “junk”

As the tendrils of the Belt and Road continued wrapping around Eurasia throughout 2017, the quality of many of Beijing’s investments was called into question. Bloomberg reported at the end of October that 60% of China’s Belt and Road (BRI) partners have sovereign debt ratings of “junk” or have withdrawn from such ratings due to a fear of poor showings.

A Belt and Road stock index?

In June, the first Belt and Road stock index was announced … but I haven’t heard a peep about it since.

Horgos / Khorgos is booming

That said, 2017 was predictably a huge year for Belt and Road infrastructure development projects.

Horgos, a new city on China’s border with Kazakhstan, was declared a robot manufacturing and export hub, and firms like Shenzhen’s Boshihao Electronics were shipped out to stock the new tech zone that’s being built there with actual companies that actually make things.

Spanning across the China / Kazakhstan border, the binational Horgos duty free zone started to boom in 2017, as China’s Belt and Road began fulfilling its own prophesies as people throughout the country begin believing in it enough to head out to remote, far western nascent boomtowns like Horgos to start up businesses.

China’s worldwide port shopping spree continued

Throughout 2017, China and Sri Lanka’s Hambantota debacle continued, reaching an apex in July when China Merchants Port Holdings took a 70% share of the Hambantota deep sea port. This takeover sparked tensions between China and India, was a political flashpoint in Sri Lanka, and even boiled over into outright violence. Needless to say, this wasn’t exactly good PR for Xi Jinping and Co. and their message of “win-win” partnerships.

(Wu Hong-Pool/Getty Images)

That said, China’s port acquisitions in other countries were numerous and mostly flew under the radar of the international media. In the past year alone, China invested over $20 billion into foreign seaports, doubling the amount they spent the previous year, as the country is now running no less than 77 sea terminals in dozens of countries around the world.

Topping this list of seaport-related developments was China Merchants’ purchase of a 90% share of the Brazilian port operator TCP Participações for nearly a billion dollars, China’s Jiangsu province signing a $300 million deal with the UAE’s Abu Dhabi Ports to develop a 2.2 million-square-meter manufacturing operation in the free trade zone of Khalifa Port, and a conglomeration of Chinese companies committing to build a $10.7 billion boomtown around a new port in Oman.

However, China’s port acquisitions in 2017 did not end at seaports. Dry ports, too, were on the radar of Beijing, as China’s COSCO shipping and Lianyungang Port took a 49% cut of Kazakhstan’s epic Khorgos Gateway dry port.

Trains, too

In January, a 200-container block train pulled out from the West Railway Station of Yiwu, in China’s coastal Zhejiang province, bound for London — an event which made it clear that 2017 would be another big year for trans-Eurasian rail development. Many new international rail lines routes emanated out from China to places like Europe, Iran, and Central Asia, and back again got their start in 2017 — including a route from the U.K. back to China which ceremoniously rolled out of London Gateway for the first time in April. To date, there are well over 40 China-initiated trans-Eurasian rail routes in operation, with new ones seemingly popping up each month.

Beyond that, over the summer China’s Export-Import Bank inked a $1.5 billion deal to provide funds to electrify the rail line from Tehran to Mashhad in Iran, which is expected to be extended into a 3,200-kilometer New Silk Road behemoth that will go all the way through Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan to Urumqi, the capital of China’s Xinjiang province. This deal laid the groundwork for over $9 billion of investment that China is planning to pour into Iran in the coming years, with the goal of boosting China-Iran bilateral trade to US$600 billion per year.

Turkey's President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, left, Azerbaijan's President Ilham Aliyev, centre and... [+]

The Silk Road becomes a network

While not having much to do with China directly, the Baku-Tbilisi-Kars (BTK) rail line finally went into operation in October. After ten years in the making, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Turkey are again connected by rail. While this development may come off as a touch unimpressive on the surface, when looking a little deeper the broader geopolitical impacts become obvious. The BTK not only bypasses Armenia — leaving the small nation even more of an isolated boulder within a flowing stream of international commerce — but also allows for trans-Eurasian multimodal routes to easily bypass Russia. To put it simply, Russian sanctions against the import or transit of most EU agricultural and food products is currently the biggest bottleneck of the New Silk Road -- something which took on additional relevance as the first test runs of European wine going to China aboard trains were successfully conducted in July.

The future is high-speed

However, the future of rail on the Belt and Road is high-speed. The long-delayed central route of the Kunming-Singapore high-speed rail line kicked off on multiple fronts in 2017 — which will enable passengers to travel between the two cities in just 10 hours when completed — and planning for the Moscow-Kazan high-speed rail line continued throughout the year. If actually built, the plan is to continue this line all the way to Beijing, allowing passengers to make the 7,769 kilometer journey in just 33 hours.

Probed by Brussels

While on the topic of China’s international high-speed rail projects, I would be remiss to leave out how development on the $2.89 billion Belgrade to Budapest HSR line was shut down by Brussels this year on suspicion that the proper protocols of the EU's public tender process may have been violated.

Hyperloops and flying trains

On that note, 2017 also saw the announcement of prospective plans to build a hyperloop between the Russian port of Zarubino and China’s Hunchun logistics zone and the China Aerospace Science and Industry Corporation claimed to have designed a “supersonic flying train” that can shuttle passengers and cargo at speeds of up to 4,000 km/h through vacuum sealed tube via magnetic levitation.

(AP Photo/John Locher)

New Silk Pipelines

While China has engaged in enhanced energy procurement operations all over Eurasia and Africa throughout 2017, one development that stands out is that Kazakhstan agreed to begin piping natural gas to China in October for a take of roughly $1 billion per year. The economic powerhouse that is China requires energy to run -- something the country has not been able to handle on its own since at least 1993 -- which is one of the main drivers of the Belt and Road.

The rise of the ‘other’ New Silk Road

2017 will also go down as the year where we see a new geopolitical alliance arising to compete with the advances of China’s Belt and Road Initiative. Building on their 2001 “special strategic and global partnership,” Japan and India have engaged in a series of mega-projects that appear to be a response to Xi's signature foreign policy power play.

Just days after Xi Jinping’s Belt and Road gala in Beijing, India and Japan announced that they were joining forces to build a New Silk Road of their own. Dubbed the Asia-Africa Growth Corridor, it is designed to “create a 'free and open Indo-Pacific region’ by rediscovering ancient sea-routes and creating new sea corridors.” Basically, it’s the same thing as the BRI, only led by Tokyo and Delhi rather than Beijing — and with trillions of dollars less in funding.

In addition to this, 2017 saw Russia, India and Japan continued working on the North-South Transport Corridor — a streamlined multimodal trade route that extends from from India to Russia, linking the Indian Ocean with the Persian Gulf with the Caspian Sea.

In this Tuesday, Nov. 11, 2014 photo, Japan's Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, right, walks past Chinese... [+]

Beyond partnerships with India, Japan also attempted to counteract China’s advances in Kazakhstan’s transportation sector in 2017 by signing an MoU with Kazakh Railways to increase the overland flow of container traffic between the Japan / South Korea region and Central Asia, the Caucasus, and Europe.

The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor is really happening - big time

Perhaps the biggest Belt and Road developments of 2017 was what happened along the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). Not only was funding for the project increased from $55 to $62 billion, but these funds are actually being dispersed and action is happening on the ground. So far, the CPEC has been overtly focused on much-needed energy projects -- $34 billon, in fact, is devoted to energy -- and coal, hydro, wind, and solar power plants are being erected all along the corridor. However, what is ultimately very different about the CPEC as opposed to the Belt and Road's other corridors -- other than the fact that it's actually being built -- is that it has a clearly stated plan. That's right, in June of this past year China and Pakistan finalized the Long Term Plan (LTP) for the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor. This shows that the Belt and Road can be more than just a vague concept; that it can be a strategy, rather than just some wishy-washy, soft power-infused initiative.

![Turkey's President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, left, Azerbaijan's President Ilham Aliyev, centre and... [+] Georgia's Prime Minister Giorgi Kvirikashvili, right, inaugurate the Baku-Tbilisi-Kars railway, at a ceremony in Baku, Azerbaijan, Monday, Oct. 30, 2017. The leaders of Azerbaijan, Georgia and Turkey inaugurated the railway line linking the Azerbaijani capital to Georgia's capital Tbilisi and to the city of Kars, in eastern Turkey. (Pool Photo via AP) Turkey's President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, left, Azerbaijan's President Ilham Aliyev, centre and... [+] Georgia's Prime Minister Giorgi Kvirikashvili, right, inaugurate the Baku-Tbilisi-Kars railway, at a ceremony in Baku, Azerbaijan, Monday, Oct. 30, 2017. The leaders of Azerbaijan, Georgia and Turkey inaugurated the railway line linking the Azerbaijani capital to Georgia's capital Tbilisi and to the city of Kars, in eastern Turkey. (Pool Photo via AP)](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!fGhH!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F16bc464a-ab4d-4b58-ac46-cade75aded23_959x1209.jpeg)

![In this Tuesday, Nov. 11, 2014 photo, Japan's Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, right, walks past Chinese... [+] President Xi Jinping during a welcome ceremony for the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) summit at the International Convention Center in Yanqi Lake, Beijing, China. (AP Photo/Ng Han Guan) In this Tuesday, Nov. 11, 2014 photo, Japan's Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, right, walks past Chinese... [+] President Xi Jinping during a welcome ceremony for the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) summit at the International Convention Center in Yanqi Lake, Beijing, China. (AP Photo/Ng Han Guan)](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!ExEH!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F18521efd-4a2a-4a94-a4ee-0d6712682b2d_958x639.jpeg)